Excerpts from *

Cotton is a cellulose fiber with molecules shaped

unlike the carbon-based protein molecules of natural dyes. So, they do

not attract each other naturally. Wool and silk molecules are liked

shaped and do not require the help of mordants to produce colorfast

results.

The early dyers believed that adding animal

proteins to the dye mix would help the penetration of the dye into the

cotton. "Animalizing," as it was called, meant adding one or

more of the following: urine, blood, milk, dung, or egg albumen. Turkey

Red, a highly valued rich, deep, brilliant red dye for yarns and fabric,

was known to use blood, dung, and urine in the dyeing process, and it

was extremely colorfast. Glancing through the back pages of old recipes

for dyers, one may find a recipe for beer…where urine was needed, beer

stimulated (shall we say) a quick source of supply. Eventually it was

recognized that animalizing proved insufficient in obtaining

colorfastness. Yet "dunging" continued to be used for the

removal of extraneous mordant until well into the 19th century, and egg

albumen continued to be used as a binder for pigment dyes.

Mordants were the answer. There are many different

kinds of mordants, but the main ones used in dyeing cotton prints were

mineral salts: aluminum, iron, tin and copper. Alum was the most widely

used, as it helped get shades of red and rust from madder. Iron was also

used a lot, with madder, logwood or by itself, to darken or dull colors

and to produce blacks and dark browns. Tin gave an extra brightness to

reds, oranges and yellows, and it resisted iron, which was a plus when

using the multiple dyes. The least mentioned mordant seems to be copper,

which was less harsh on cotton than tin, but could still be harsh. It

brought out green tones, and darkened dyes, generally. An analogy of

mordant dyeing would be a bridge over water. The mordant forms a bridge

between the dye and the cotton, enabling the dye to travel into the

molecule and bond with it . . .

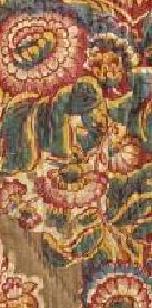

Many

reds, pinks, rusts, browns and purple dyes came from the root of the

madder plant . . . Many

reds, pinks, rusts, browns and purple dyes came from the root of the

madder plant . . .

Colors produced from mineral dyes include Prussian

blue, manganese bronze, chrome yellow, orange, blue, or green, antimony

orange, iron buff and teal green. There were two ways these pigment

colors could be fixed to cotton. Early on, egg albumen was used as a

binder for lighter colors, and blood was used for the darker colors.

Gluten from wheat and lactarine from milk were other binders, but all

binders needed heat and an acid to make them colorfast. Ultramarine blue

was made in this manner. In the other method, the pigment was printed

directly onto the fabric and then passed through a second dyebath,

usually of potassium or alkali, to cause a chemical reaction between

them on the surface. For example, chrome orange was produced when chrome

yellow was passed through an alkaline treatment, and Prussian blue came

from iron and potassium . . .

The primary method of Indigo dyeing was called

vat dyeing. A vat is a chemically reducing dyebath . . .

Simply adding more dye to the bath would not produce a darker shade of blue. It

required repeated submerging followed by oxygenation. If an area were to remain

white it would be covered with a resist paste made of wax or wheat, to keep the

dye from penetrating in . . .

Eventually, stable direct printing of indigo was possible in the last quarter of

the 19th century. Glucose utilized indigo in such a way that the reduced version

combined with steam would fix the color. German scientist, Bayer, first

synthesized indigo in the 1880s, patenting it in the early 1900s. Commercial

dyeing with synthetic indigo didn't begin until 1897. It essentially replaced

the use of natural indigo by the early 1920s . . .

* For complete article and pictures, click on:

Vintage

Fabrics - IN SEARCH OF WARP ENDS. Found

at: http://www.fabrics.net/joan1002.asp

|