|

The expansion westward brought on the need for signing quilts and autograph books. It

gives me pause each time I remember that westward expansion at that time may be a

move to Ohio from Massachusetts! The far western states were still a journey too

far for most families to undertake until the California Gold Rush. The lure of

gold in the 1850s changed the minds of many Easterners who came across treacherous

miles of mountains and

wilderness to find their riches. Research tells us few quilts were actually made

while on this treacherous journey, but many were brought to keep them warm on

the way and fill their new home. (Treasures in the Trunk, Quilts on the

Oregon Trail, Mary Bywater Cross, 1993)

The early signature quilts were based on friendship and made as memorials for

the leaving family. The 1840s and 50s was

the era of sentimentality. Poetry verses, autograph books, music and

illustrations reflect a leaning toward the romantic and nostalgic. A look

to one's mortality led to the desire to capture through the written word the

essence of a friendship. Journals, diaries, scrapbooks, autograph albums, photos, and signed

quilts reflect this sentimental time. Many of these memory saving hobbies were

taken up once again in the late Victorian period, but not signature quilts.

Instead, women would place their memorials on silks and velvets in crazy quilts.

Printed commemorative ribbons, embroidered pictures and sayings, sun printed

photos and other memorabilia embellished these patchwork quilts so popular

between 1876 and 1900.

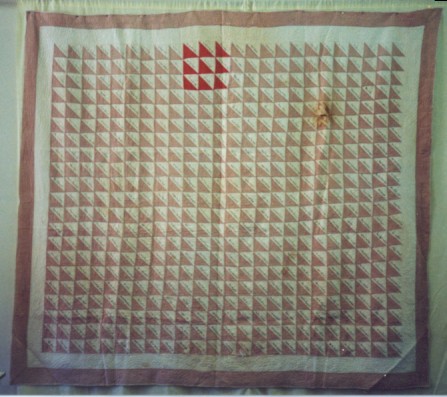

ca. 1870 church fundraising signature quilt bought in eastern Missouri

(detail view below)

When money was needed to help soldiers in the Civil War, women developed the

practice of raising funds with quilts. These quilts raised money via raffles

or by charging the signer a fee per signature. Sometimes an entire family would sign

one block each. More often a

quilt was signed with hundreds of signatures and then

raffled off, bringing in as many funds as possible from a single quilt. Stories are told about quilts being re-donated by raffle

winners, two or three times over, so that the one quilt could make as much money as

possible for the cause they all believed in. When money was needed to help soldiers in the Civil War, women developed the

practice of raising funds with quilts. These quilts raised money via raffles

or by charging the signer a fee per signature. Sometimes an entire family would sign

one block each. More often a

quilt was signed with hundreds of signatures and then

raffled off, bringing in as many funds as possible from a single quilt. Stories are told about quilts being re-donated by raffle

winners, two or three times over, so that the one quilt could make as much money as

possible for the cause they all believed in.

Women were known to place their political and religious beliefs on quilts. The

glorious Baltimore album quilts have sayings, bible verses, and drawings inked

on many of the blocks. These quilts were not made to be raffled that we know of.

Instead, they were made as a special gift for a particular individual in the

community that was respected for their contribution to the community in some

way.

Their name, the names of the quilt makers, and other information or sentiments would be placed on

Baltimore Album quilt blocks; some, not all, but particularly the center

block.

19th Century Ink Signatures

Signature quilts are a phenomenon that occurred before the discovery of a perfected non-fading, non-bleeding,

indelible ink. Several "recipes" were developed between 1834

and 1840. Britain gave three patents between 1837 and 1840.

A new understanding about the cause of the signature

quilt fad and its relationship was discussed in Barbara Brackman's recent

(Sept. 11, 2005) digital newsletter.*(Reprinted with permission from

Barbara

Brackman, The Quilt Detective: Clues in the Needlework, 2005, digital

newsletter, #29 - Inked inscriptions.) In this issue she

revisits her earlier research that credited Payson's invention of an indelible

ink in the mid-1830s as main reason friendship quilts with

signatures came into fashion in 1840.

"[Dr. Margaret] Ordoñez’s research into ink

composition indicates that there is no such clear-cut date for non-corrosive,

commercial inks. She notes 'the search for permanent inks that did not damage

paper and fabric was ongoing throughout the nineteenth and into the twentieth

century.' She includes a reference as late as 1913 lauding a welcome new

non-corrosive ink for laundries . . . Ordoñez found several patents for carbon

inks issued in Britain in the late 1830s."

Barbara writes that in light of this research it

seems unlikely that it was a change in ink that led to the fad for signing

quilt blocks. Her stance now is that the era at that time was more influential

than the changes in ink's indelibility than she had previously thought. The style of signing friendship blocks with ink begins as early as

1839 in Barbara's database, but quilts were signed with ink beginning in the

early 1830s.

(I highly recommend subscribing to Barbara's digital newsletter.

Read more about it here

www.barbarabrackman.com)

Margaret T. Ordoñez is a professor in the Textile

and Clothing Department at the University of Rhode Island and she heads up

their conservation lab. For more detailed information about inks and their

effect on fabric, read her research paper “Ink Damage on Nineteenth

Century Cotton Signature Quilts,” in Uncoverings 1992,

(San

Francisco, American Quilt Study Group, 1993).

Iron sulfate and nut gall (gall forms around wounds on the bark of oak trees and

to encase gall wasp's eggs)

were combined to form the basic ink used throughout most of the 19th and part of

the 20th century. In the early years, the problem arose when the tannic acid in

the gall would harden cellulose fibers in fabric and paper. A chemical

reaction called hydrolysis would occur causing the cellulose fibers to degrade.

It also caused damage to occur overtime. Water and light helped the degrading

along. The earliest signed blocks show the remaining ink smeared or almost

invisible. People tried some other rather interesting elements to

make ink. These included indigo, Prussian blue, silver nitrate, madder, potash

with wood tar, and lampblack mixed with either linseed oil, or borax and

shellac. India ink, made from carbon, and sometimes mixed with diluted

hydrochloride acid, seemed to be the most resistant to fading when wet and

soapy.

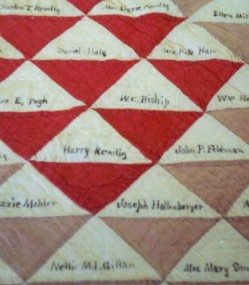

ca. 1870

fundraising signature quilt close up

Signatures, drawings, dates,

and verses were tiny in the early years. They were applied to the fabric using

stencils, stamps or freehand. Stencils were made from copper, tin or nickel. A

lady would have one made for herself that portrayed her sense of style. It may include a design, like a feather or fancy

circle around her name, or just be simple block letters. These were used to

label their clothes and linens too, a common practice when women washed their

clothes in public places. Stamps, with changeable letters were more economical

and common. The letters were lead, the stamp metal, with a wooden handle. These

stamps could have a decorative oval shape, which encircled the changeable

letters. The most popular form of signature was freehand, either by a hired

calligrapher or by the maker of the quilt block. Signatures, drawings, dates,

and verses were tiny in the early years. They were applied to the fabric using

stencils, stamps or freehand. Stencils were made from copper, tin or nickel. A

lady would have one made for herself that portrayed her sense of style. It may include a design, like a feather or fancy

circle around her name, or just be simple block letters. These were used to

label their clothes and linens too, a common practice when women washed their

clothes in public places. Stamps, with changeable letters were more economical

and common. The letters were lead, the stamp metal, with a wooden handle. These

stamps could have a decorative oval shape, which encircled the changeable

letters. The most popular form of signature was freehand, either by a hired

calligrapher or by the maker of the quilt block.

|

Reference books

Listed below are some books I recommend for both the quilt maker and the researcher on

signature quilts.

To make your own signature or album quilt check out these books, and if

you scroll down you will find books that contain historical accounts of

signature quilts.

Keepsake

Signature Quilts,

by Sally Saulmon

Click

here for my book review on this book.

The Signature Quilts, by Pepper Cory and Susan McKelvey

Friendship

Offering, Techniques & Inspiration for Writing on Quilts, by Susan

McKelvey

History

Books

Most of the following books are not currently

in print, so check your library, , the interlibrary loan services, and used

bookstores

For

Purpose And Pleasure : Quilting Together in Nineteenth-Century America,

by Sandi Fox

Forget Me Not, by Jane Bently Kolter

Remember Me, Women and their Friendship Quilts

by Linda Otto Lipsett

Hearts and Hand, by Elaine Hedges, Pat Ferrero, Julie Silber

Shared Threads, by Jacqueline Marx Atkins

The Baltimore Album Quilt Tradition , by the Maryland Historical Society

(may be available through them)

History

Articles in:

Quilt

Digest

, Vol. 5, "Fragile Family Quilts as Kinship Bonds" by Ricky

Clark p. 1-19

Pieced By Mother,

edited by Jeannette

Lasansky, "Mid- 19th Century Album and Friendship Quilts" by Ricky

Clark, p. 77-86

Quiltmaking

in America, Beyond the Myth, edited by AQSG, (compiled from previous

Uncoverings

-

AQSG's journal)

"Signature Quilts: 19th Century Friends" by Barbara

Brackman, p. 20-29, and in the same book

"A Century

of Fundraising Quilts, 1860-1960," by Dorothy Cozart, p. 156-63

Another Style

of Album Quilt Harriet

Powers: Her Life and Story Quilts - A freed slave tells stories through her

quilting. Written by Anne Johnson.

|