|

Cocheco produced dress goods, furnishing fabrics, novelties and printed

patterns, such as stuffed toys from 1827 to 1912.

In the last quarter of the 18th century, Philadelphia became the first textile center in America. John Hewson, a

calico printer and designer, trained in England, emmigrated to Philadelphia to

become one of the earliest American printers on cotton that was colorfast. His wood block printed

chintz panel prints were for the center of quilts in the medallion design. These

panels were also cut apart and appliquéd down on whole cloth tops. Hewson

printed entire bedcovers in similar style to Indian Palampores, but his style is

unique. He printed large vases and baskets of flowers, as well as borders and

corner motifs.

Cotton cloth was imported and weaving was still done by hand and at home until around 1810. The effort to establish a machine-spun yarn and thread culminated in 1793, when Samuel Slater and Moses Brown opened the first machine cotton spinning mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.

Longstanding, successful printwork companies began at Waltham in 1813. The

largest complex in Lowell, MA, began in 1822. Some factories manufactured their own cotton cloth, at 64 threads per inch, while others ordered it from a weaving mill, ready for printing.

By the end of the 1830s, almost all home manufacturing of cloth was over. The technology for rapid manufacturing and printing of cloth was in the US. Fabric was easily obtainable and affordable, but the quality was not as good as that from Britain or France. Today, when an early-American printed chintz is compared with its British counterpart, the colors of the former are washed out and dull, whereas the latter are bight and beautiful.

Cocheco Manufacturing Company started out as the Dover Cotton Factory in 1812.

They did not begin producing cotton fabric until 1815, when they spun yarn and

changed their name to Dover Manufacturing Company. The printing of calico fabric with

wooden blocks started in January 1826, but cylinder printing started soon after, in early 1827.

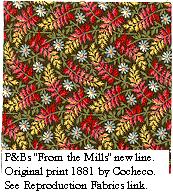

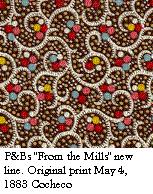

P&B's Reproduction Fabric - From the Mills October 2001

This proved to be financially draining. So, later that year, the printworks was incorporated separately. This is when Cocheco was born. By the end of 1829, all the spinning, weaving and printing operations were housed under their name.

Plain cotton goods were prepared through many processes. Heating and singeing removed fibrous elements left on after weaving. Bleaching followed, with a series of chemicals to make the cloth light before the printing and dyeing processes. “After treatment” processes were applied after printing, such as dyeing, brightening and drying. Finally, there were “finishing processes,” such as stiffening, clearing, stretching and packaging, before bolting and shipping the fabric to market. The market consisted of consumers, retailers, jobbers and manufacturers.

Printwork companies relied on marketers to take over at some point. They provided a variety of services ranging from selling the goods, to helping determine which prints will sell, to financing. At

Cocheco, Charles Everette was the agent from Lawrence & Company. The design effort was a mutual one, between the agent and printworks company, but the final decision was up to the agent. The agent would secure samples, do a market survey among consumers, and send their version to the printworks for engraving the rollers. They had a finger on what was selling and what was not, because they were in the greater metropolis of Boston. Cocheco’s factory was in Dover, NH, a rural

town. Goods were shipped to ports all over the world. Lawrence & Co. also served as the quality control personnel, examining the fabrics for consistency of color, prints and fabric quality. Cocheco maintained a high position in the marketplace.

By the 1870s, Cocheco printed an average of 25 million yards of fabric annually By the 1870s, Cocheco printed an average of 25 million yards of fabric annually

The New England states and south to Philly, as well as the Chilean seaboard in South America, were the primary areas at this time. The number of yards produced nearly doubled by the 1880s, and sales were all over the world. Oriental and Japanese designs exerted a great influence at this time, including the yin-yang symbols and Chinese pictographs and ideographs on prints of the day. Egyptian motifs were just as popular at the end of the decade, as indicated by prints with hieroglyphics, crescents and moons. This new decade saw the return of large scenic designs on white or light backgrounds. Americans were not likely to be the primary designers and relied heavily on European designers. This was so common; companies formed specifically to offer selected designs from Europe to American printwork companies, via fabric samples, drawings and plates. Two such companies were Homo & Cie Co., and Jacob H. Summer.

France held the lead for taste and originality in the latter half of the century and was called “the world’s studio” by textile printers. It did not take long for their designs to show up on American store shelves; about two to three weeks. The copies were not exact, but almost. Something as small as a leaf color could be all that changed. America chose prints solely based on their salability, not their design principle. In fact, considered more important than design, was color. In the late 19th century, schools of design were established in the US, after the discovery of synthetic dyes, which greatly broadened the colors available to textile printers. Printers experimented relentlessly with the new synthetic dyestuff until troubles began around WWI, when trade with Germany (the primary manufacturer of the finest synthetic dyes) stopped.

Cocheco Prints

Cocheco produced dress goods, furnishing fabrics, novelties and printed patterns, such as stuffed toys from 1827 to 1912. Records of their goods are archived at the American Textile History Museum, in Lowell, Mass. The museum's Cocheco records and samples date from 1855-1917, with the majority being from 1880 to 1890.

Cocheco’s target audiences were the middle and working classes. Cotton fabrics, shirting, cambric, percale and madder-style prints, were used for informal clothing in rural settings throughout the late 19th and early 20th century. Printed satine and cambric were the recommended dress fabrics for the upper class’s daytime socializing, according to the fashion gurus. Young women wore lawns and batistes in the summer. Lawns, a lightweight sheer linen fabric, were made in France, and later came to England and America. From the 1870s to mid-1880s, they were a popular fabric for border prints, a style for which Cocheco became known. The bordered edge was three inches wide. Small geometric designs or flowers could compliment the border throughout the print.

Furnishing fabrics made of cotton were also relegated to less formal rooms as decor. Cretonnes were considered “charming.” Cretonnes were large-scale prints, like early chintz florals, but never glazed and sometimes in a twill weave, or textured weave. Furnishing fabrics used more colors, and were more complex and time-consuming to produce. These style trends were slower to change.

A favorite pattern of Cocheco looked like bubbles rising through the air, or strings of pearls. Purple fabrics with small print motifs in black or white, was considered a staple in ladies wardrobes. Paisley shawl prints and Oriental motifs were found on shirting, muslin, batistes, satine and fancies. Chocolate prints were white or gray motifs on a chocolate brown background. Quite popular in the 1880s, the dark brown could make the gray appear light blue.

Satines purposely imitated silk’s smooth and lustrous finish and were the most popular novelty fabric at Cocheco in the mid-1880s. Satines often imitated Japanese indigo prints. As the 1880s ended, they made prints with dull and lusterless finishes, challises and cashmeres. A finishing process called calendaring was used to achieve both of these looks. A shiny finish went out of style at the end of the decade, as did border and scenic prints.

Foulards were also silk look-alike. Cocheco printed foulards onto a variety of plain weave fabrics with a high gloss, as opposed to a twilled silk. In fact, they made many different “fakes” during the 1880s. These were printed imitations of

fibrous or woven fabrics or wools. Fakes included the look of seersucker, damask, tweedy wool, silk, three-dimensional designs, oxford cloth, stippling, and fluffy textured looks.

There was a change in printwork companies color palette, following the discovery of synthetic dyes, such as aniline in 1856 for purple (not used on cotton until the early 1860s) and alizarin in 1869 for Turkey Red. (I reviewed a new book titled, "MAUVE, which is on the invention of these. Click my Book Review link on the main page). At Cocheco, they used these, along with natural dyes such as logwood, lamp black, and indigo, throughout the 1880s. In 1887, a fire devastated the company, destroying all of their machines and ultimately closed them down for an entire season. This led to further changes in their palette, from deep browns, dark reds and pretty pastels, to more complex and varied colors on prints. Pinks became more violet. Shades of copper and bronze appeared. New shades of blue appeared, from royal, to turquoise, to gray.

Throughout most of the 19th century, Cocheco made a shirting print with a tiny vine and floral all-over pattern, in one or two colors, with a miniature blue or red dot on some of them. They also produced eccentric geometric designs, fancies, one and two-color stripes, and conversation prints featuring different sporting and hobby equipment, animals, and other common objects of the day in the last quarter of the 19th

century.

By 1900 Cocheco printed more than 50 million yards of fabric each year. Pacific Mills had taken them over in 1909, and shut down the printing operations three years later. They continued to spin and weave the cloth for Pacific Mills until 1940, when the doors permanently closed.

References:

"English and American Textiles: From 1790 to the Present," Mary Schoeser and Celia Rufey, Thames and Hudson, Inc., 1989

"Just New From the Mills: Printed Cottons in America," Diane L. Fagan Affleck, Museum of American Textile History, 1987

"The American Quilt, A History of Cloth and Comfort 1750-1950," Roderick Kiracofe with Mary Elizabeth Johnson, Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. 1993

“Printed Cottons in Victorian America: Cocheco Manufacturing Company,”

Diane L. Fagan Affleck, SDJ, Winter, 1984

|